An Extremely Post Mortem of Splinter

Warning: this is a long one. Get a snack.

Five years ago today I released my one and (likely) only indie game1. I called it Splinter as a reference to augments that the main characters in the game surgically insert into their bodies to gain superhuman abilities. I had done a lot of hobby work in film over the years and I thought it would be fun experiment to try to combine film and video games in a novel way. There had been other titles that used video clips as part of their gameplay, but typically they used full screen overlays to play video as if you were watching TV. My spin was to embed clips directly into the world objects. A poster on the wall of a room would be your canvas, for example. The core idea was environmental storytelling combined with literal video storytelling in the environment. My elevator pitch was “Gone Home meets Enter the Void2,” although a more accurate (but less pithy) pitch is “7th Guest minus the puzzles meets Enter the Void.”

In November of 2017, my tenure at Telltale Games abruptly ended. Suddenly I had some time on my hands, so I decided while looking for my next job I was going to start production on Splinter. I had a crew of film makers that I had worked with over the years on various projects. One of them, Justin Lanelutter, was a writer who agreed to help me with the script. I had a production team, scared up some actors, and things started moving. On June 23rd of 2018, we started filming.

In many ways, making Splinter felt like having a child, only I didn’t get to fob the hard parts off on my wife. Some day I will be ready to talk about the details of the production process, but for now I will just say that the damn thing nearly broke me. After the first filming session, which ironically went so well that I was buzzing about it while we were striking the set, I learned that my director and my director of photography were now mortal enemies. I ultimately had to fire the director, and two days later found out that the set we had lined up for the roof deck scene fell through 3 days before filming. On top of all this chaos, my then three year old son was going through an extremely difficult phase where he wasn’t able to successfully attend a preschool. These were not good times. Fortunately, thanks to the herculean effort of the team I pulled together, we managed to muddle through the remaining three weekends of filming and wrap. Once that was done, all I had left to do was make the game!

I spent about two years working on this, doing nights and weekends while holding down a full time job and being a dad. Things did not go smoothly. As Valve succinctly put it once when they announced a delay: “Making games is hard.” Towards the end of 2019 I started experiencing major burnout. Thanks to some late reinforcements, I was able to get it to what I thought was a shippable, if imperfect product. My motto is “Ship it, do better next time” and I definitely leaned on that to make the launch call. There were sections that were extremely rough, but I hoped that there was enough of the core product in there to get some grace from the indie community, and more importantly I desperately needed to not work on it anymore.

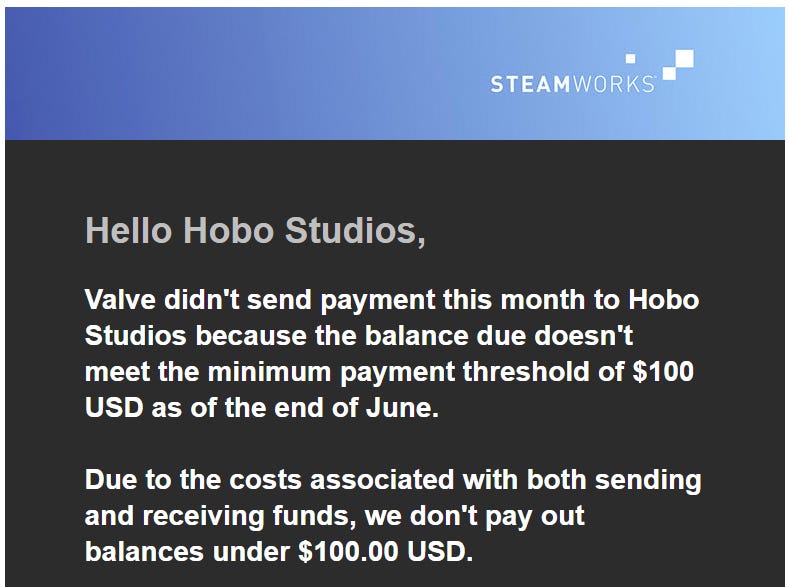

Thus came the launch on August 21, 2020. I am not going to pretend this was something it wasn’t. It was pretty much a total failure. One fun thing most people probably don’t know about: if you have a game for sale on Steam, and you don’t sell enough to gross $100, they won’t send you any of the money. Which is reasonable. But the fun part is that they send you an email every month you fail to clear that bar. At the risk of Chang-ing myself, That means that every month I get to see this message:

I think after about the seventh straight one we can dispense with the bookkeeping. Squiggly line ain’t going up anytime soon. It’s like if somebody dumped you and then texted you every month to remind you that you aren’t getting back together.

The main failure, though, wasn’t the financial one. I labored under no illusions how that was going to play out. The real failure is that the things I thought Splinter brought to the table that might resonate with a niche audience - the experimental interplay of film and gameplay - clearly did not land with many people. Playing through it again recently it is pretty easy to see why. One of the roughest sections of the game was also one of the first scenes you play, and should have just been cut altogether. I suspect it was too much to ask for people to grit their way through that and most people rightfully bailed. So that’s the bad news.

The good news, for me, is that there is a lot here that I absolutely love. Usually when I make something I have a grand vision of how it should be and when I finally manifest it I am underwhelmed by how I fell short. For better or worse, Splinter is as close as I have ever gotten to actualizing what was in my head.

Traditional game developer postmortems follow a “What went Well/Wrong/Lessons Learned” format. If I tried to write a “What went wrong section” this would turn into a novel. As for Lessons Learned, it would probably be a different novel.

So in lieu of the traditional format, I will instead give you an incomplete list of Things I Love about Splinter. Starting with:

The Trailer

The goal here was to introduce the game space and central theme of the game. The monologue by Sam - the visionary of the hacker collective in the story - gives you the essence of what the narrative is about, which can basically be summed up by Edward Wilson’s top-shelf quote:

“The real problem of humanity is the following: We have Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions and godlike technology.”

I wanted it to be druggy, dreamy, and surreal and I think it hits all of those beats. I’ve heard critiques that it doesn’t show the gameplay at all but this title isn’t about the gameplay so I am sticking to my guns. I don’t think I would change much about this.

The UI Particles

While I was in preproduction, I stumbled upon a reddit thread about a new type of particle spawning in Unity. This feature allowed you to place an unrendered image in the world and spawn particles from the non-alpha portions of the image. This was a big thing for me in particular, because one of the design constraints I was putting on myself for Splinter was as much as possible I wanted everything in the game to be diegetic. No HUDs, no life meters, no menu screen where you can watch the clips as full screen videos in sequence3. You see touches of this throughout the game. The song you hear in the dream sequence tutorial at the beginning is what is playing on your ipod when you wake up. The rhombic dodecahedron4 you use to fly through the dream sequence is a beloved object sitting on your night table at the beginning. Keeping the immersion and everything contained in a cohesive world was a key pillar for me. I only break this rule in a couple places: I ultimately relented and made standard pause menu to exit because my in game stuff was too confusing, and the opening credit sequence music is not in world, although I was able to add a little hook for that. When you (spoiler alert) get shot in the opening police chase, the beeping from the EKG reader seamlessly slides into the beeping from the opening song.

This constraint was going to be hard to execute for UI though, certain game elements require SOME text to steer you as a player. Like a START button, or how to control the player. Being able to use the particles to convey UI beats meant I could get the information across and still keep everything in the world.

If I had my druthers I would have made the particles from the start button form directly into the spirit orb that guides you at the beginning, but otherwise I am satisfied with them.

The Level Design

Hoa Nguyen did a phenomenal job with the art direction, and I enlisted Chris Caprio to do the level design for the game and he did an unbelievable job pulling the elements from the set into the in-game warehouse.

The times where I was able have the video world and game world nest in on each other were the best. Like when you first go from the living room to the hackspace, and the video on the door plays as you move towards it, showing Sam opening that door in the video to the room you were also entering. For all the pain I experience playing through the more excruciating things I apparently allowed to ship, its bits like these that bring me back off the ledge.

The Dina Reveal at the End

OK I am kidding this one. With the possible exception of the police sequence at the beginning, this was probably the biggest disaster of the final product. A natural result of both bad design and burnout on my part. My goal for this beat was to have a moment like the “We have to go back, Kate!” hammer from the Season 3 finale of Lost. Up to this point, all the movie clips you watched were scenes from the past, filling you in on the backstory of who you were as the main character, how you wound up in this warehouse, and why you ultimately were shot and killed. This clip takes place in the present, after you are dead, and is Dina’s chance to say goodbye to you.

All well in theory. The problem was I knew ahead of time I wasn’t going to have a budget to animate a 3d model for Dina to give the soliloquy, so I went for this foolish idea of filming Dina in a tight closeup and carving out UVs on the face model to use as a texture canvas. The haters said I couldn’t do it and they were correct. What came out is one of the more cursed images I have ever been responsible for.

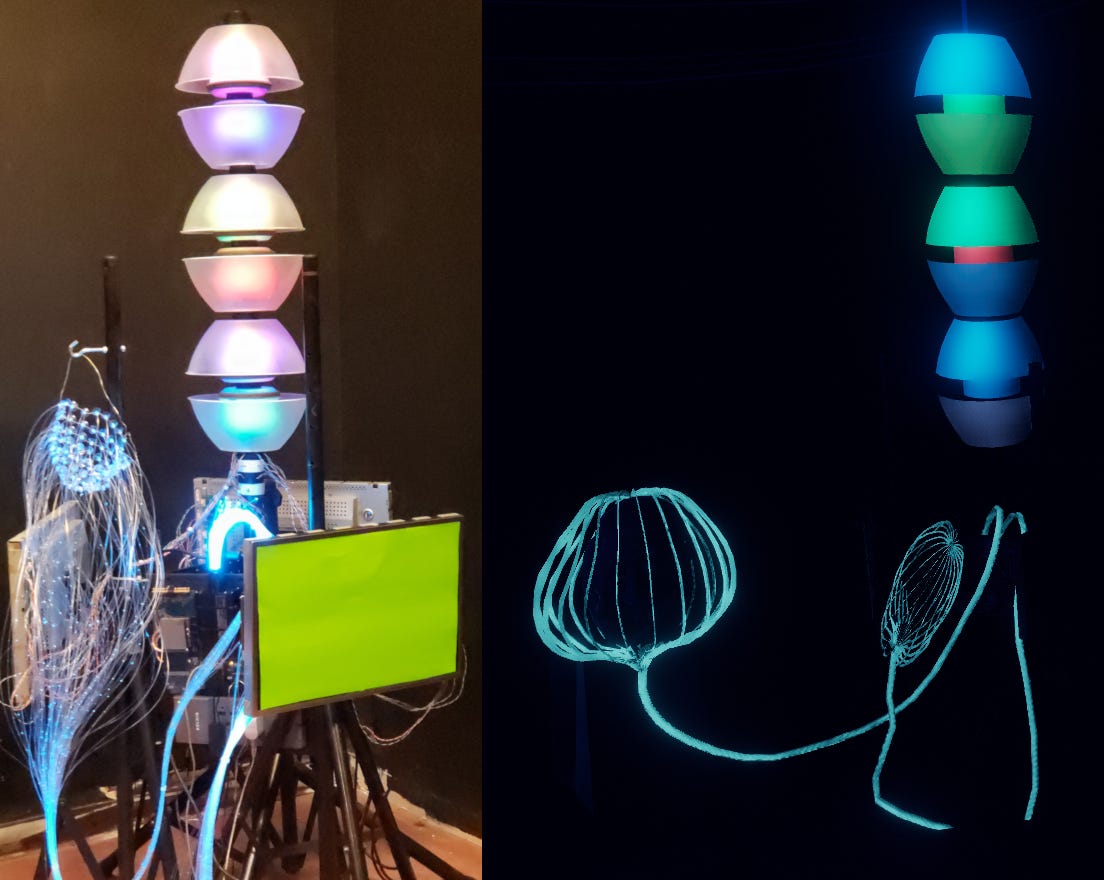

The Cender Device

The key prop of the movie, the machine that Sam uses to harvest the consciousness of the unsuspecting ravers at the parties they throw, was a sculpture that I commissioned from a friend who absolutely I could imagine being a part of the Ascenders, Brian Krawitz. It was a functional art piece that is now enshrined in my trophy area.

The Acting

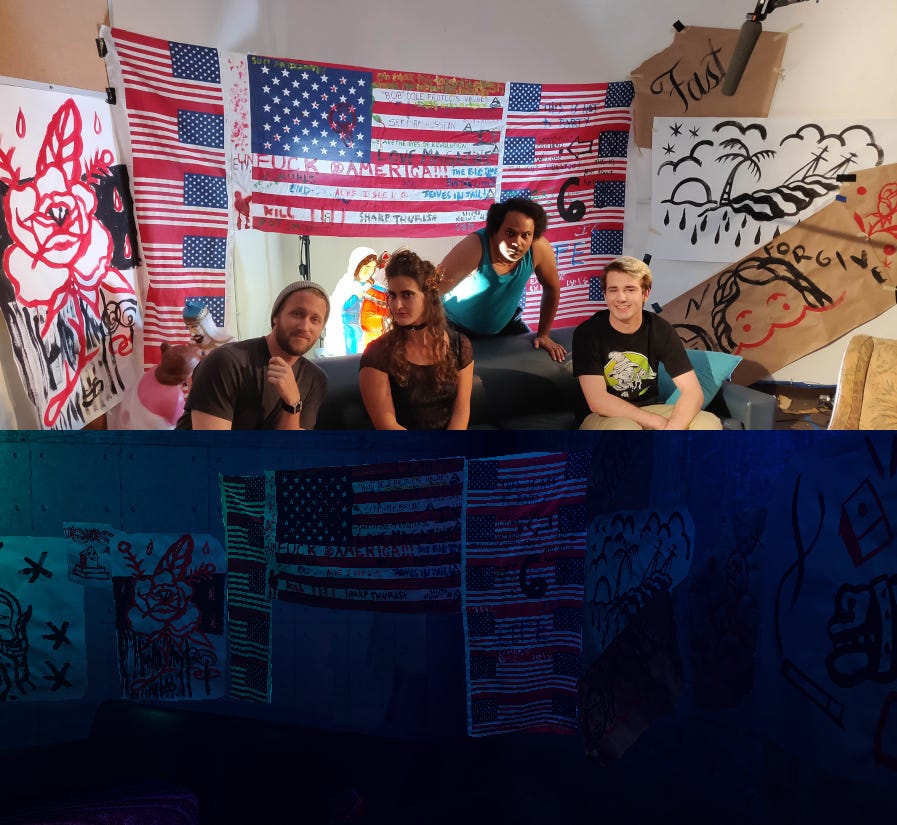

Considering that I pulled together a cast on the cheap from craigslist and friends, I am really happy with how well they performed. Marcus Sams had the most impossible role, portraying the spastic lunatic Tink5, and he pulled it off very well, combining both the manic energy and the elusive “smart guy who is oblivious that other people exist” vibe into a dangerous, fun soup. Hunny Bunnah6 crushes the role of Natalie, leader of the Ascenders. Smart, tough, does not care at all about your problems, just trying to get things done and keep idiots away from her organization. Beau Williams nails that calm arrogant messianic role of Sam as the yin to Tink’s yang. James Brennan, for whom this was his first role, perfectly captures that likable, dorky, in-over-his-head innocence of the main character Mason, and Kaya Mey is delightful as Dina, the sweet, accidental siren who inadvertently lures Mason to his death.

The Ending

Right after the unpleasantness of the Dina reveal, you are awkwardly thrust upward to look at the sky. From there though, this is one of my favorite game endings ever. Pulling yourself up from star to star, having them cascade past you as the final voiceover plays. Cut to black and Smoke Like Ribbons plays as we roll credits. It is everything I wanted for a closer.7 The stars aren’t that far in the span of an eternity.

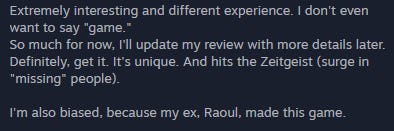

Maybe this is the game developer equivalent of an Andy Kaufman sketch, which seemed at times like they were specifically crafted such that he was the only person he expected to find his act entertaining. All I know is it pleases me to no end that this weird, messy thing is in this world and other people can poke around in it. Many, many thanks to everyone who helped make this. I will leave you with my favorite Steam review, which I think does a really good job of capturing the experience. But before you read this, I think it is important for you to understand that I am not, did not work with, nor have I ever personally met, anyone named Raoul.

The game was released on August 21st. I screened my lone indie film that I made on August 20th 10 years prior. I would have lined up the dates but alas Steam won’t allow you to release a game on a Thursday.

Most people in the video game world know about Gone Home, the game where you search an unexpectedly empty house for clues as and slowly piece together the narrative surrounding it. Much fewer people know about Enter the Void which is a shame because it is a masterpiece of cinematography. I don’t know if it is a good movie per se, but I haven’t been able to get it out of my mind since I first saw it.

Something my friend and producer for the project Erik Braa desperately wanted. Sorry Erok!

A late add from Carl Muckenhoupt, for whom that particular polygon is a spirit animal. Carl joined the project towards the end when I was running on the fumes of my fumes and I don’t know how I would have gotten over the finish line without him.

Tink was based off a friend of mine that I lived with for a few years who was without question the craziest person I have ever met in both good ways and bad. As I described to friends when he was my roommate: 9 times of 10 I want to strangle him. But that 10th time is magic.

When we were working together, Hunny Bunnah went by the stage name Hunny Bunny. When I was putting together the credits for this at the end of development I reached out to her and asked her if she wanted to go by her real name or her stage name. She replied “I’m most often listed in Films on IMDB as Hunny Bunnah, so please list me as Hunny Bunnah.” I was not prepared for the credit name to get weirder as a result of that discussion!

Astute listeners will even catch a subtle nod to Pink Floyd here.

Really fascinating story of what it takes to make a game. But I think some images are missing bc there are some big white spaces...